Peer Powered, Cash Logistics

|

Conversion of Cash |

|

|

Float Management |

|

|

|

Cash Supply |

|

Cash-in-Transit is Broken

Traditional cash-in-transit (CIT) services in Australia, which involve armored vehicles and security personnel transporting cash and valuables, are facing significant challenges that signal a system under strain. These failures stem from a combination of declining cash usage, rising operational costs, security risks, and inefficiencies that have left the industry struggling to remain viable. A simpler, innovative solution like Peer Cash—centered on crowdsourcing supply and collection through trusted agents—could address these issues by reducing complexity, cutting costs, and improving accessibility. Below, I’ll explore the key failures of traditional CIT methods in Australia and why a shift toward a streamlined alternative is increasingly necessary, drawing on insights from recent news articles.

One of the most glaring issues with traditional CIT is its economic unsustainability, driven by the rapid decline in cash transactions. As reported by the ABC in March 2024, cash usage has plummeted from over 60% of purchases in 2010 to just 13% today, accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic and the rise of digital payments. This shift has hit companies like Armaguard, which controls about 90% of Australia’s CIT market, hard. The company warned that its wholesale cash transport business—moving money from the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) to banks—was no longer profitable, even after merging with competitor Prosegur in 2023. This merger, approved by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC), was meant to shore up the industry, but just four months later, Armaguard required a $10 million lifeline from its parent company, Linfox Group, to stay afloat. The article highlights how the big four banks (ANZ, Commonwealth Bank, NAB, and Westpac) were poised to intervene, underscoring the systemic fragility of a service reliant on a shrinking cash economy.

Security risks further compound the problem, exposing the vulnerability of traditional CIT methods. News24 reported multiple violent incidents in recent months, including a December 2024 cash-in-transit heist in Motherwell where a G4S vehicle was targeted, and another in Korsten where a security guard was killed in a shootout. Earlier, in October 2024, two guards were injured during a heist on Durban’s N2 highway, after which the public looted the damaged vehicle. These incidents illustrate not only the physical danger to personnel but also the logistical chaos that follows, disrupting cash flow and public safety. In Australia, while such extreme violence is less common, the reliance on armored vehicles and armed guards still presents a costly and risky model, especially as cash volumes dwindle, making each trip less cost-effective.

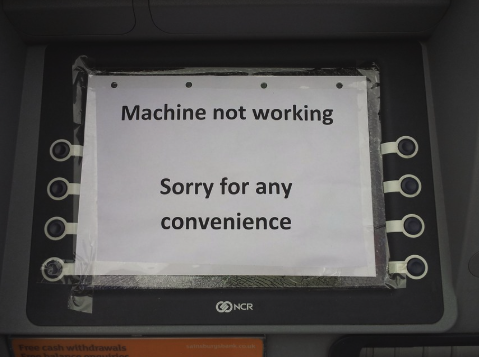

The infrastructure supporting cash access is also crumbling, adding pressure to the CIT system. A 7NEWS report from October 2024 revealed that Australia’s bank-owned ATMs and branches have halved in seven years, dropping from 19,508 in 2017 to 8,836 by mid-2024. Despite this, RBA data showed a 2.7% increase in ATM withdrawals from July to August 2024, indicating that many Australians still rely on cash, particularly in regional areas. This mismatch—fewer access points but persistent demand—strains CIT services, which must cover vast distances to service a shrinking network. News.com.au noted in October 2024 that major banks have closed branches and ATMs en masse, while a January 2025 article criticized a bank’s $2.50 fee for assisted cash withdrawals, calling it a “cash grab” amid cost-of-living pressures. These developments highlight a broken distribution chain that traditional CIT struggles to support efficiently.

The ACCC’s interventions reflect the industry’s desperation to adapt. In May 2024, it authorized the Australian Banking Association (ABA), banks, and retailers to collaborate on sustaining cash distribution after Armaguard’s warnings of collapse. By July 2024, news.com.au reported interim approval for a multimillion-dollar deal involving the big four banks, Coles, Woolworths, and others to fund Armaguard, giving it 12 months to restructure. ABA chief Anna Bligh emphasized the need to “keep cash moving,” but the temporary nature of this bailout—coupled with Armaguard’s near-monopoly—suggests a Band-Aid solution rather than a long-term fix. TheConversation.com warned in April 2024 that Armaguard’s potential insolvency could hasten a cashless society, a scenario the RBA seeks to avoid as cash remains a critical backup when digital systems fail.

This is where a solution like Peer Cash could step in. By crowdsourcing cash supply and collection through trusted agents, it sidesteps the heavy overhead of armored vehicles and security teams. Instead of centralized, high-cost operations, Peer Cash leverages a decentralized network of individuals or small businesses—think local shopkeepers or community members—acting as intermediaries to handle cash securely and efficiently. This model could slash transportation costs, minimize security risks by reducing high-value targets, and restore cash access in underserved areas where banks and ATMs have vanished. It mirrors peer-to-peer lending concepts (as defined by Investopedia in August 2024), where intermediaries are bypassed for direct, trust-based transactions, but applies it to physical cash movement.

The need for simplicity is clear: traditional CIT is bogged down by legacy systems ill-suited to a digital-first world with niche cash needs. Peer Cash’s promise lies in its agility—using existing community networks to save time and fix a fractured system. While news articles don’t directly mention Peer Cash, the struggles of Armaguard and the closure of cash infrastructure scream for an alternative. Critics might argue that ensuring trust and security in a crowdsourced model poses challenges, but the status quo—marked by violence, inefficiency, and bailouts—proves the old ways are failing. A leaner, community-driven approach could be the lifeline Australia’s cash system needs, balancing modern realities with the enduring relevance of physical currency.